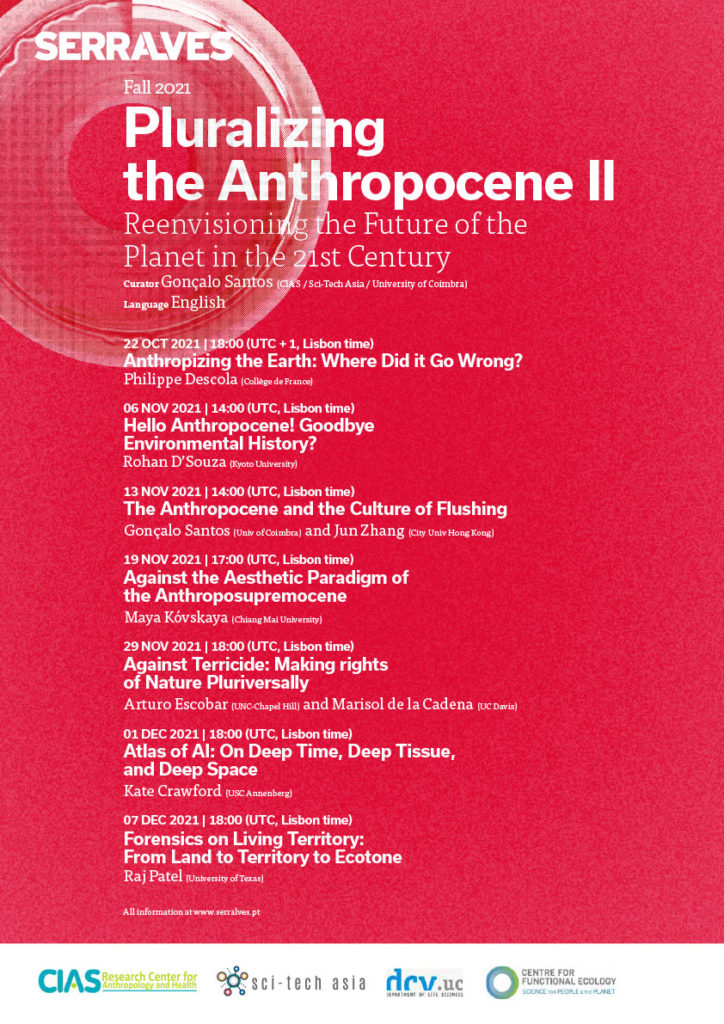

Curatorial Project

Pluralizing the Anthropocene II

Reenvisioning the Future of the Planet in the 21st Century

Watch Now

About

There is no doubt that the environmental impact of the human planetary expansion reached new levels with the rise of the modern industrial world and the “Great Acceleration” that took place after World War II. In this talk, we make the case that one of the best ways to capture this catastrophic shift to an era of increasing anthropogenic environmental uncertainties is to look at the global spread of a system of human waste management based on flush toilets and centralised sewers. In the last two hundred years, this water-powered system of waste disposal has become a core symbol of modern civilization and a basic requirement of public sanitation in urban settings, but it is a very expensive solution that cannot be afforded by all and has significant environmental costs. These costs have become increasingly salient in the current age of environmental uncertainties and increasing levels of water scarcity. At a time when the world is facing a water crisis of gigantic proportions, it is no longer clear whether it is a good thing to continue using water as a medium for the disposal of domestic—and industrial—waste, especially when there is significant evidence pointing to the limitations of existing sewage treatment technologies. The fact is that flushing away the problem does not solve the problem; it only compounds it by moving it to another place and turning it into someone else’s problem. This institutionalised culture of flushing and forgetting is not circumscribed to matters of urban sanitation; it is a founding value of contemporary throwaway economies and one of the key reasons why it is so difficult to challenge the “take-make-waste” linear model of the world economy and its unsustainable assumption that the planet has infinite resources. We link the development of this unsustainable culture of flushing and forgetting to the history of industrial capitalism and its increasingly wasteful practices of production and consumption, and we draw on historical and ethnographic research in China to show that it is possible to develop alternative models of human waste management that help reduce the pressure on existing water resources, while contributing to the creation of a more circular economy where everything—including human waste—is recycled and resources are regenerated.